Giorgio Vasari: architect, great artist, historiographer, and sometimes gossipy amateur.

- Il Mio Salotto

- 24 set 2021

- Tempo di lettura: 5 min

Aggiornamento: 1 dic 2021

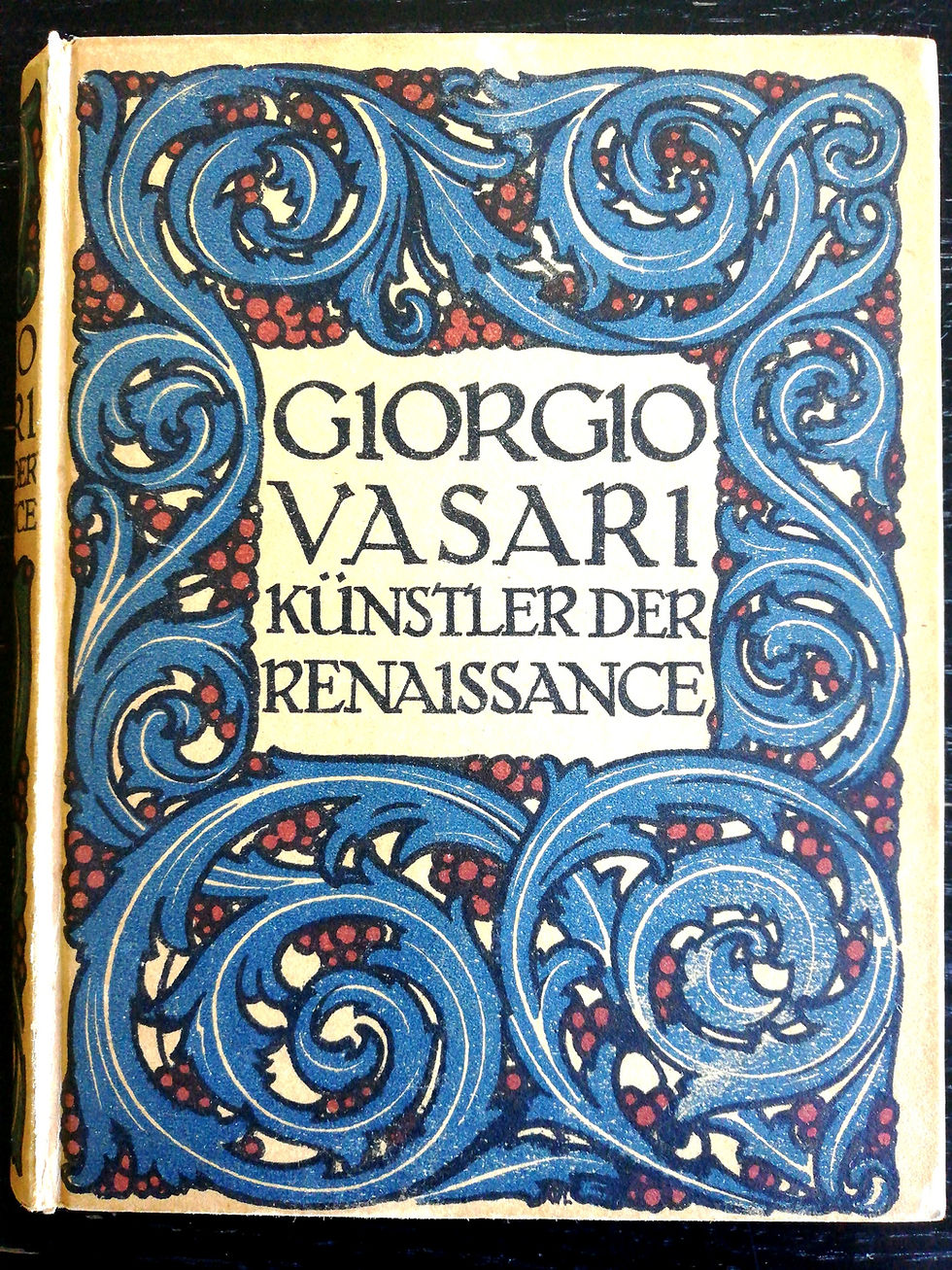

In previous articles, we have talked about a Swedish artist, Hilma Af Klint, a Spanish artist, Picasso, and today it is the turn of an Italian. Perhaps not everyone knows him, because he may not be as famous as Giotto or Modigliani, but if you have been to Florence, you will certainly have heard of him, and if you have gone to the Uffizi Gallery and walked along the Vasari corridor, you know that they are both projects by the artist I am talking about today, Giorgio Vasari.

Giorgio Vasari is a Tuscan, born in Arezzo on 30 July 1511, and he is not only a painter, but an all-around artist as he was also an architect and historian, and to this day we can say a nice "gossiper".

Now I will tell you about him in a little more detail.

The Vasari, so-called by art history scholars, was the son of a textile merchant and a noblewoman, and already as a child, he was able to have an artistic education, in fact, he was able to attend the workshop of a stained glass painter, attend lessons in humanistic education and approach architecture, even creating the base of the organ of the Duomo and beginning to become aware of the influences of Michelangelo. The whole family had encouraged him to study and draw from an early age.

When he was a teenager he went to study in Florence, and luck mixed with chance led him to associate with members of the Medici family, thus broadening his humanistic education with the scholar Piero Valeriano and going as often as possible to the workshop of Andrea del Sarto and to the drawing academy of Baccio Bandinelli.

Unfortunately, a few years after his arrival in Florence, Vasari had to return to Arezzo to take care of his mother and siblings, as his father, his greatest fan and ally, had passed away.

After this sad event, which led him to have a religious crisis, Vasari began to feel crazy and out of place, and began to travel the length and breadth of Italy collecting information on artists in various cities, thus discovering and loving art throughout Italy. Information that would form part of the project he was working on: The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.

Traveling far and wide, like many artists, Vasari had a tangled love life. He was madly in love with Maddalena Bacci by whom he had two illegitimate children, but to avoid scandal at the time, he married her 14 years old younger sister, relegated to live alone in the family home in Arezzo, and used to cover up his adulterous and passionate relationship with Maddalena.

From the age of 34 to 36, Vasari was in Rome and part of the Farnese court where he became increasingly close to Michelangelo. Thanks to those years in which he was always surrounded by intellectuals he was inspired to compose the first draft of the Lives.

His wife, however, was very young and he decided to return to Tuscany, where he had his manuscript printed and dedicated it to Cosimo Dé Medici, hoping that with this move, he would be able to befriend him and benefit his career.

So it was. The move of the dedication and the definitive return to Arezzo bore fruit. Cosimo de' Medici commissioned Vasari to carry out several works in Florence, including the restyling of the Palazzo Della Signoria, the design of what was to become the Uffizi, and the famous Vasariano corridor, the one that connects the Palazzo Pitti to the Palazzo Della Signoria.

With his book, Vasari became to all intents and purposes 'the first Italian art historian'. He invented art historiography and inaugurated the genre of the encyclopedia of artistic biographies, coining terms such as Renaissance, Gothic and Modern Mannerism. His writings remain to this day an inexhaustible source for researching biographical information on various artists, even if the biographies are interspersed with gossip and amusing anecdotes. This is why Vasari is often referred to as a 'gossiper'. A bit of GOSSIP...

The most famous is the story, told by Vasari, of the young Giotto who drew a fly on the surface of a painting by Cimabue and which the older master repeatedly tried to chase away.

Take Sandro Botticelli instead. Without Vasari's book, we might not know that Sandrino really liked to joke around or about the pranks the young artist pulled. In fact, he loved to organize real jokes involving other people and making jokes all the time, thus making his workshop a cheerful place to work and spend time with his assistants.

Giorgio Vasari also wrote about Raffaello Santi, who had a very favorable life from the start. In fact, his father Giovanni did not want him to be nursed by the wet nurse but by his mother Magia.

Vasari compares this to Michelangelo's less gentle beginning when he was sent away from home to be nursed "by peasants and plebeians" and then says:

"Raphael's character was sweet and heavenly, Buonarroti's was gruff and wild".

Another "scoop" by Vasari concerns a work by Michelangelo, the crucifix: he obtained permission from the Augustinian monks of Santo Spirito to study corpses. Thus Michelangelo Buonarroti often went to Santo Spirito to dissect corpses, practicing this practice which was 'illegal' for the Catholic Christian religion at the time. When in the seventeenth century Caravaggio took as his model a well-known prostitute, who died by drowning, it is not accidental: only for the corpses of the very lower classes was this practice allowed on the bodies, also because no one went to claim them. Vasari says that this polychrome wooden crucifix was given by Michelangelo himself to the prior of the Augustinian monks of Santo Spirito as a thank you for the opportunity to dissect corpses, and therefore the possibility of studying anatomy from life. The Crucifix is the only certainly attributable, documented work of Michelangelo Buonarroti in polychrome wood, mentioned in the Lives. Vasari always maintained that sculptures made from this poor material and with this artistic technique were minor works.

Another curiosity about Michelangelo, mentioned by Vasari in his book, concerns his nose.

According to Giorgio Vasari's descriptions, although he was "Divine" in his art, Michelangelo was not so in real life, in fact, he had a strong temperament that often resulted in aggression and this led him to fight with another artist, Pietro Torrigiani, who could no longer stand Michelangelo's constant teasing and broke his septum with a punch in the face.

It is impossible to verify the truthfulness of these anecdotes, perhaps dictated by Vasari's imagination, but they certainly make the book more fluent and enjoyable, humanizing the figure of the art historian.

Ilaria Puddu